THE NAPOLEON JACKET : MILITARY FORM AND CONTEMPORARY FASHION CIRCULATION.

12/31/2025

Author: Soukita

01.1 Why We Keep Returning to Military Dress

Certain garments never fully disappear from fashion. They pause, recede, then return with new meaning. Military dress is one of those sources. Its appeal has less to do with nostalgia than with clarity.

Uniforms are designed to be understood instantly. They compress authority, hierarchy, and discipline into a visual system that can be read at a glance. Structure does the work. Proportion controls posture. Repetition and symmetry create order. Even after uniforms leave active service, the underlying silhouette remains recognizable.

Fashion returns to military dress because that recognizability transfers. When the original rules and ranks are removed, the form still communicates. What remains is a set of shapes and cues that can be reused, adapted, and recontextualized across different eras without requiring the institution that produced them.

The Napoleon jacket sits at the center of this cycle. Today, the term is used to describe a recognizable type of military-inspired jacket that appears repeatedly across runways, resale platforms, and social media. While the label is applied loosely, the look itself remains consistent enough to be grouped and recirculated as a category.

01.2 Anatomy of a Napoleon Jacket

The Napoleon jacket does not describe a single historical uniform, but a category defined by shared features. These typically include a short, tailored silhouette, a high stand collar, dense front closures, and decorative braid or cord applied symmetrically. Historically, materials such as wool and felt provided rigidity, while metal buttons, bullion braid, and embroidery denoted regiment, rank, or ceremonial status.

In military contexts, each design element communicates specific information. Braiding reinforces closures and identifies units. Buttons signal affiliation. Collars control posture and reinforce uniformity. Construction functions as a visual system rather than decoration alone. When these elements migrate into fashion, their regulatory purpose dissolves, but their visual clarity remains. The jacket continues to read as structured and intentional, even when detached from military hierarchy.

01.3 History of Name

Military uniforms are built to be read quickly. Their shapes and surface details are standardized so that authority and affiliation could be recognized at a distance. When those cues move into civilian dress, the original rules fall away, but the look remains recognizable. This persistence allows the jacket to endure as a form even when it is no longer tied to a specific regiment, country, or uniform code.

The name “Napoleon jacket” is not a historical uniform term. It developed as a modern fashion label used to describe jackets that resemble nineteenth-century European military styles associated with the Napoleonic era, particularly short, structured officer silhouettes with dense buttoning and decorative braid. The label spread through fashion media, resale listings, and social platforms as a practical way to group visually similar garments under a shared, searchable category.

Once this naming convention became common, it reinforced the type. A jacket did not need a direct connection to Napoleon Bonaparte to be labeled “Napoleon” if its visual cues aligned with what the term had come to signify. In this way, the name functions as a tool of circulation rather than historical classification.

02.1 From Uniform to Culture: Early Civilian and Symbolic Use

As military uniforms move out of active service, their visual language continues through civilian and ceremonial contexts. Marching bands, civic parades, and state pageantry preserve the structure and ornament of military jackets, including symmetrical fronts, high collars, decorative braid, and metallic hardware. In these settings, the jacket’s form remains intact while its function shifts away from regulation and combat.

Performance culture accelerated this transition. In 1967, The Beatles adopted military-styled band uniforms during the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band era. Drawing from British military and marching band dress, the costumes used braid, epaulettes, insignia, and medals as visual markers rather than symbols of service. Authority became image, and structure became spectacle.

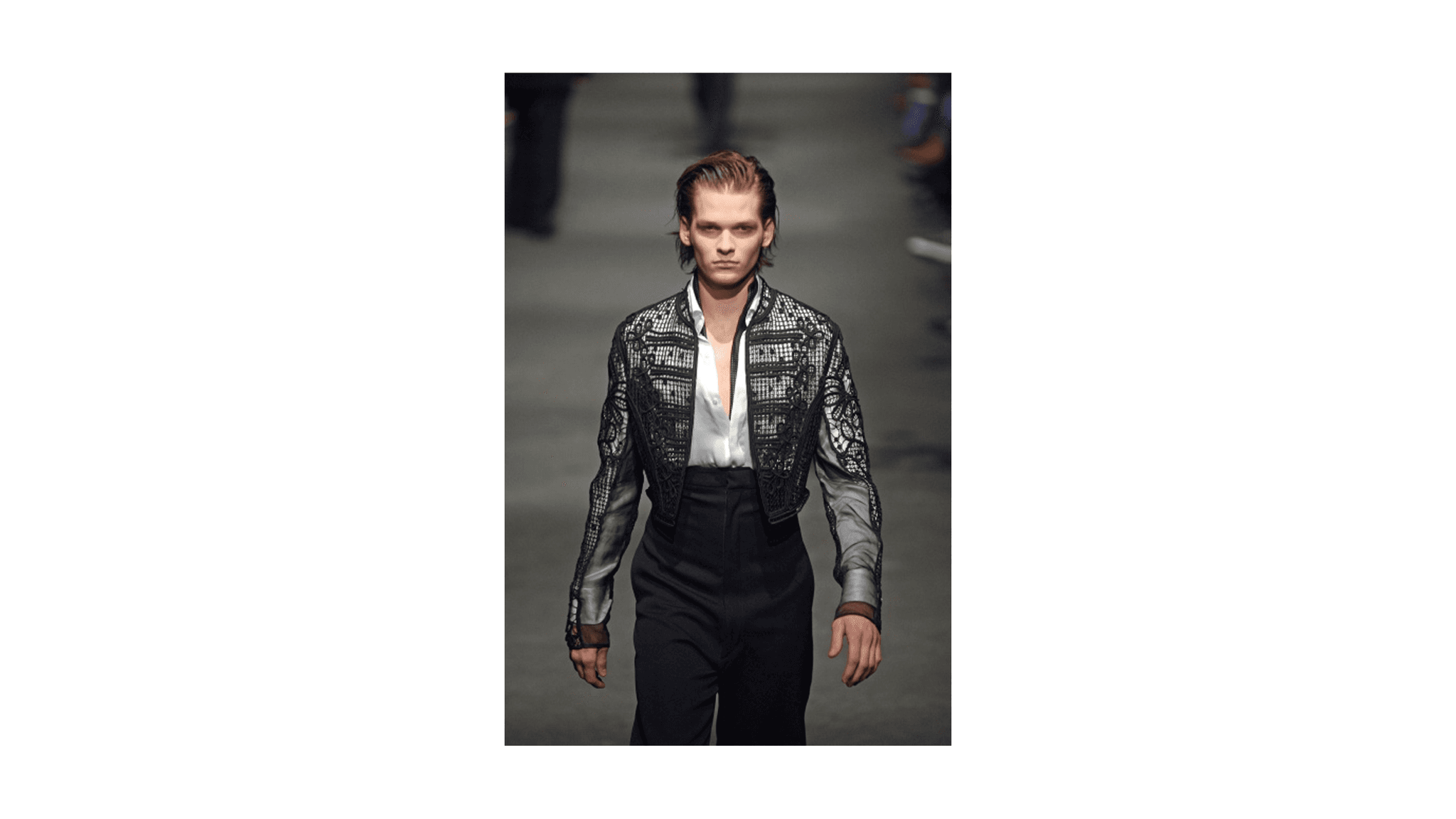

Fashion absorbed this symbolic shift more formally in the early 2000s. At Dior Homme, Hedi Slimane’s Spring/Summer 2006 menswear collection introduced sharply tailored, cropped jackets with officer-style collars and dense closures. Military reference was reworked through proportion, becoming a defining visual language of the decade.

A few years later, Balmain under Christophe Decarnin extended the silhouette into late-2000s womenswear. The Spring/Summer 2009 collection featured rigid shoulders, heavy braiding, and metallic embellishments. These jackets moved quickly from runway to editorials and celebrity styling, cementing the form within the fashion imagery of the period.

Alexander McQueen worked with similar language during the same decade. In Fall 2006 menswear, hussar-inspired figures appeared on the runway. In Fall 2008 womenswear, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, military tailcoats and frogging re-emerged as part of McQueen’s theatrical vocabulary. In each case, military dress functioned symbolically rather than literally.

Runway presentation does not initiate renewed interest in isolation. Its role is to formalize silhouettes that are already circulating visually. Recent fashion coverage has explicitly linked contemporary military-inspired jackets to reference points from the 2000–2010 period.

Coverage of Spring/Summer 2026 collections documents this continuity. Cropped and more open interpretations of braided military jackets appear at Alexander McQueen and Kenzo, while additional reporting groups hussar-inspired jackets among notable seasonal statements at Ann Demeulemeester and Vaquera.

02.2 Why Napoleon Jackets Still Feel Modern

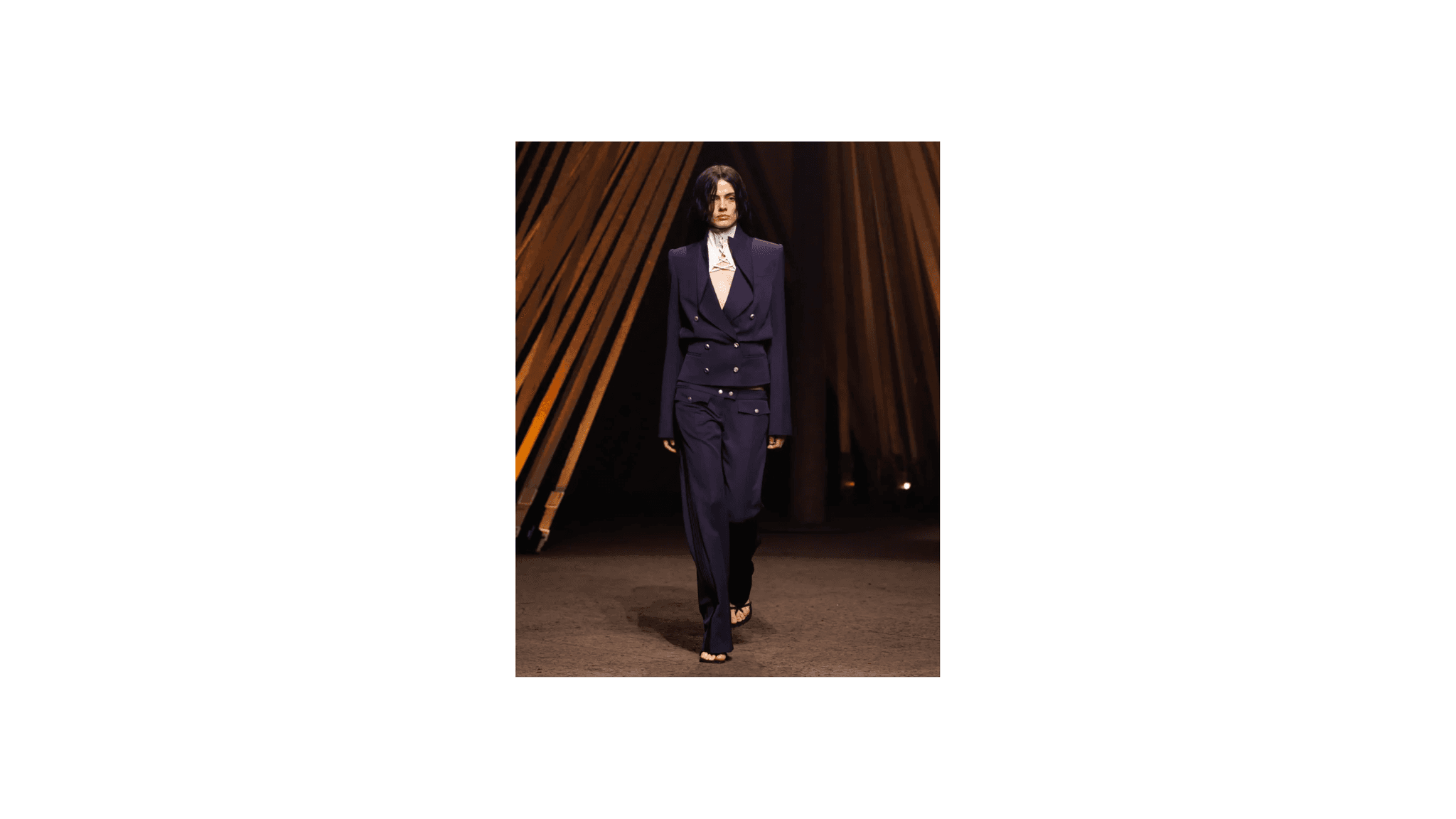

Contemporary interpretations of the Napoleon jacket continue to rely on structural clarity. Standing collars, dense closures, and defined shoulders create a compact and legible silhouette that organizes the body without additional styling. These features allow the jacket to be recognized quickly across runway presentation, editorial photography, and digital formats.

The silhouette circulates across menswear and womenswear contexts with limited alteration to its core structure. Variations typically occur in proportion, scale, or material rather than through fundamental redesign. As a result, the jacket functions as a transferable form rather than a garment tied to a single wardrobe or prescribed use.

While military dress historically carried associations with ceremony, hierarchy, and institutional authority, those associations shift when the jacket is worn outside a uniformed system. In civilian and fashion contexts, ornament and hardware no longer indicate rank or enforce command. They persist instead as visual references detached from their original function. The jacket’s structure remains intact, but its authority becomes symbolic rather than operative.

03 Closing Reflection

The silhouette of the Napoleon jacket remains legible because it is the ultimate visual shorthand for power. Yet, in the hands of the everyday, that power is neutralized through repetition and reimagining. What was once a uniform of exclusion has become a canvas for inclusion—a way of wearing the history of the institution without being beholden to it. It is no longer a garment that defines a soldier; it is a form that allows the individual to reclaim the theater of authority.