FASHION IN PARTS: MODULARITY AS DESIGN LANGUAGE

1/15/2026

Author: Soukita

Modularity in fashion does not begin as a futuristic idea. It begins as a recurring use problem.

Certain areas fail first. Collars collect dirt. Cuffs fray. Linings hold sweat. A coat that works outdoors feels heavy indoors. A layer you need at 5 p.m. becomes something you have to carry by 11. When a garment is built as one sealed object, wear tends to spread through the whole piece.

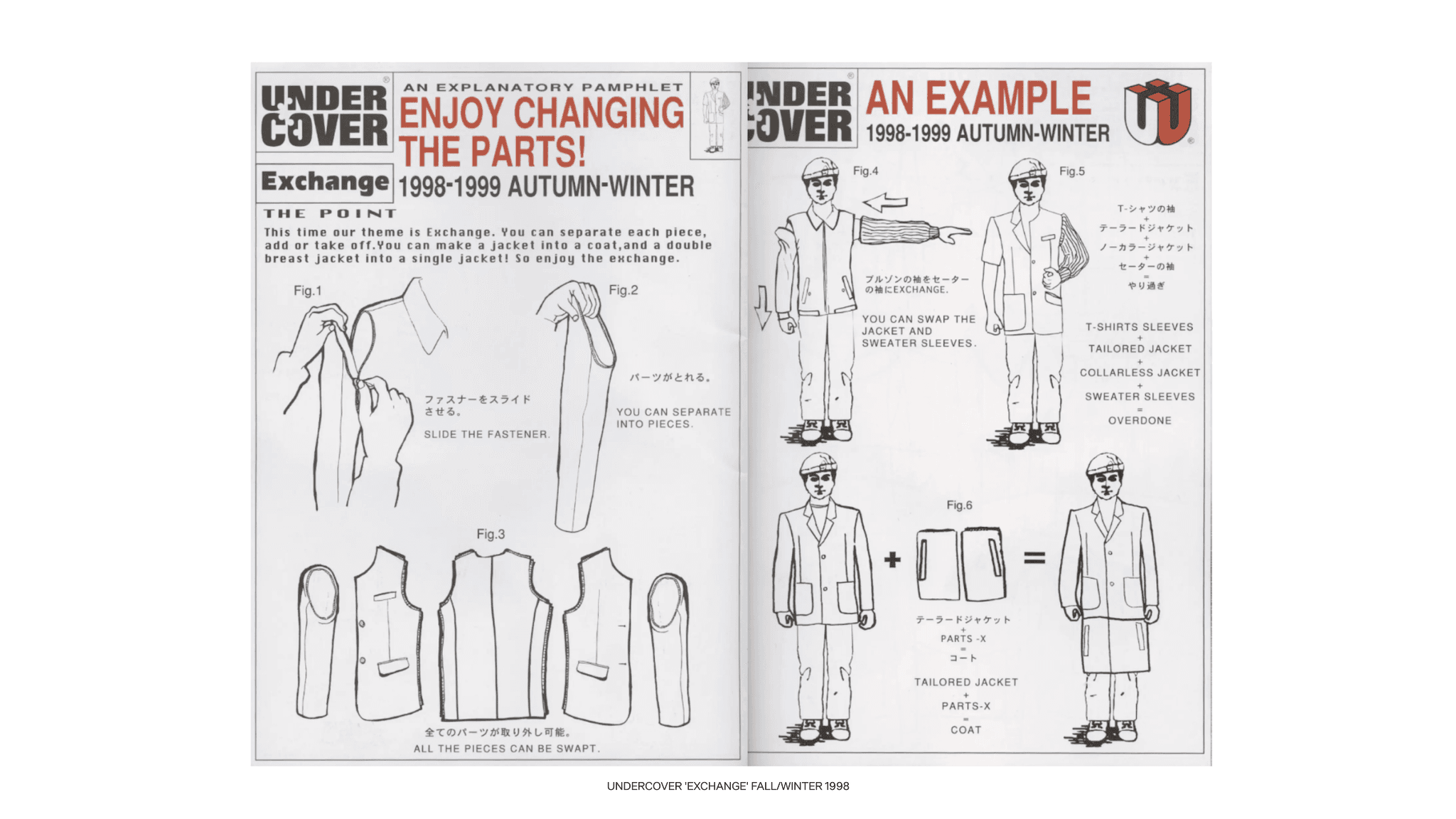

Modular design treats clothing as a set of components, built around connection points. The change can be visible or concealed, but the principle stays the same: the garment is designed to stay complete in more than one form.

A practical way to scan for modularity is to look for three things:The part that changes. The connection point. Whether it is meant to be used repeatedly.

THE FIRST MODULAR HABITS

Detachable collars are an early example of the logic: the collar was often the first part to need cleaning or replacement, so separating it from the shirt extended the life of the main garment. The same thinking appears in removable linings, replaceable components, and added protective layers, designed to keep garments working through repeated wear.

In couture and formalwear, modularity shifts from cleaning to context. The change is small but deliberate: cover the arms, fill in the neckline, add the layer, then remove it later without the piece looking unfinished. An evening dress in The Museum at FIT’s collection (c. 1830, originally owned by the Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna) includes sheer oversleeves the museum notes are probably removable, a feature that would have helped the wearer move from day to evening.

By the late 1800s, “transition dresses” formalized the same logic into a system: one skirt paired with multiple bodices, with add-ons like removable neck fillers or lower sleeves described in period dressmaking contexts.

What matters is that the change is designed in. The garment has more than one intended configuration, and each one reads finished.

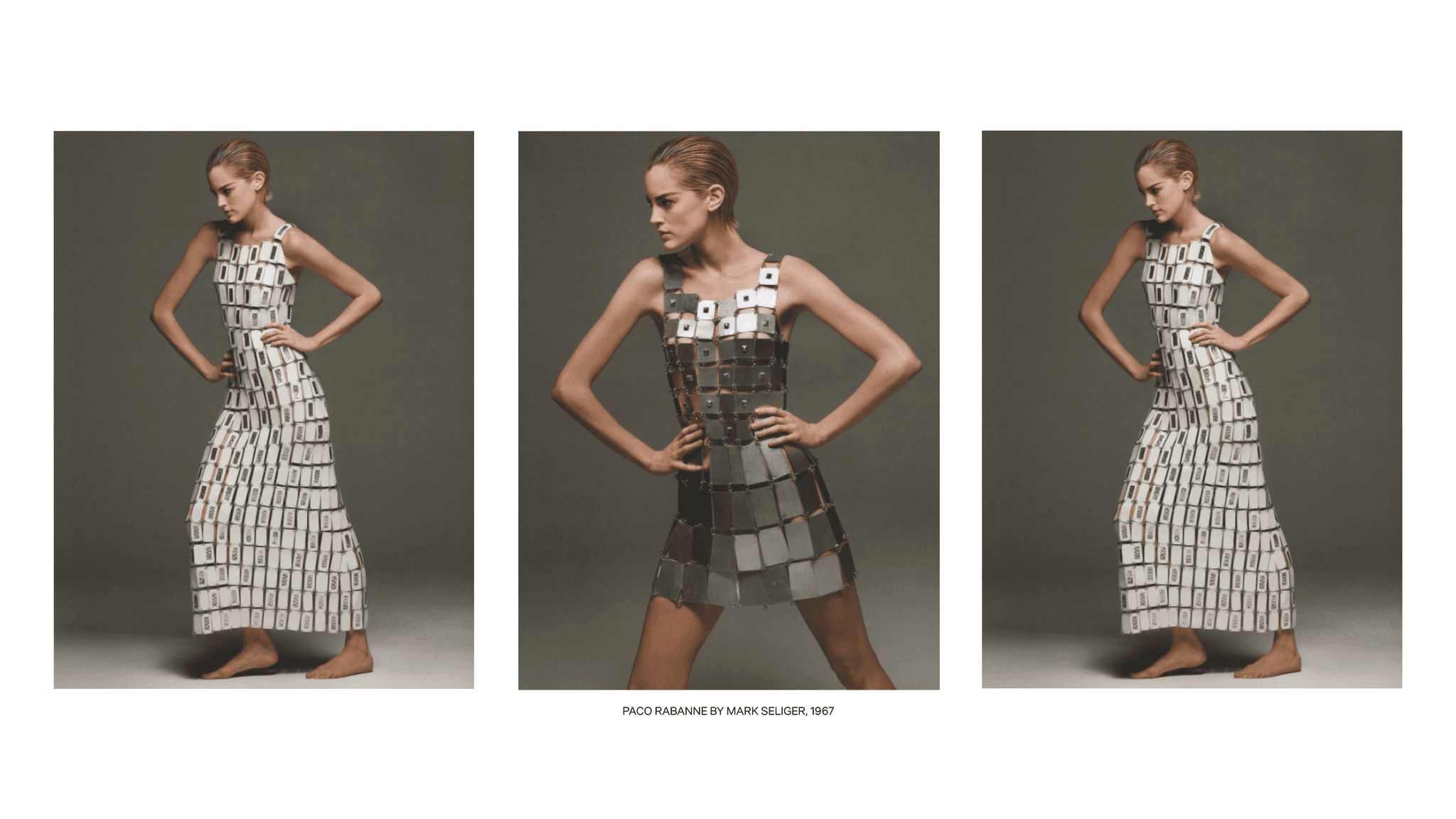

RABANNE, BUILT IN LINKS

In the 1960s, modularity became easy to see because the connection moves to the surface. Paco Rabanne’s early work is often cited because garments are assembled from repeated units, linked through rings and hardware. The join is not hidden inside a seam. It becomes part of the surface, making the garment read as an assembly rather than a single cut-and-sew object.

In the 1960s, modularity became easy to recognize because construction moved from the inside of the garment to the surface. Paco Rabanne defined this shift by building clothing from repeated units linked with metal rings and hardware. He chose to expose these connections instead of hiding them within traditional seams. By making the joins visible, Rabanne transformed the garment into a structural assembly that looked entirely different from a standard sewn object.

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LjnuHmxRbxI (10:53-12:04)

Hussein Chalayan “One Hundred and Eleven,” Spring/Summer 2007

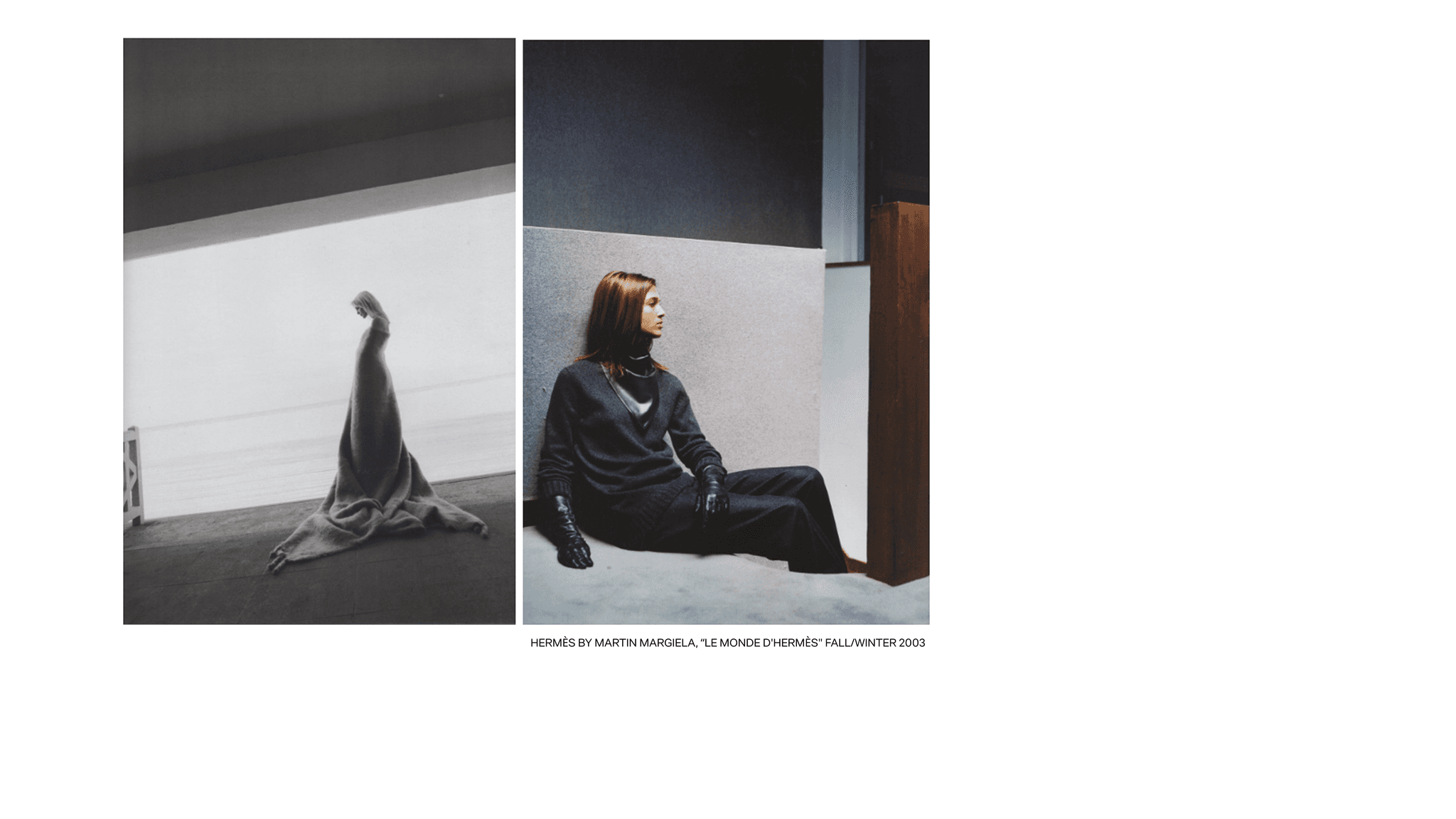

TRANSFORMABLES IN LUXURY

Modularity in luxury is often hidden. The goal is not to create a “convertible” gimmick, but a piece that looks finished. That is why transformable outerwear keeps showing up in late 1990s and early 2000s references: coats that shift between sleeved and sleeveless forms, collars that detach cleanly, linings finished to function as a real outer layer. Margiela’s years at Hermès are a clear reference point, including the Spring Summer 2003 trench with detachable sleeves and alternate armholes, worn as a standard trench, a cape, or a vest.

On the runway, modularity sometimes becomes movement. Hussein Chalayan’s Spring Summer 2007 show One Hundred and Eleven showcases garments visibly shifting shape during the walk, moving through different silhouettes in sequence.

Modularity can function as a collection of separates rather than a single adaptable item. Designers build these sets so that every piece remains compatible with the others. This allows for seamless layering and recombination while preserving the overall proportions of the outfit. Sandra Garratt’s Units and Multiples are a scaled example, sold as coordinated jersey components meant to generate many outfits from a limited set of parts.

Modularity often operates through two distinct ways: One garment, multiple forms.Multiple garments, one system.

MODULARITY AS FUNCTION

Changing environments reveal the true value of modularity by highlighting the need for flexible systems. Outdoor gear has worked this way for decades: trousers that zip into shorts, jackets built as shells plus removable liners, hoods that stow into the collar, pieces designed to be opened, closed, and re-layered as conditions shift.

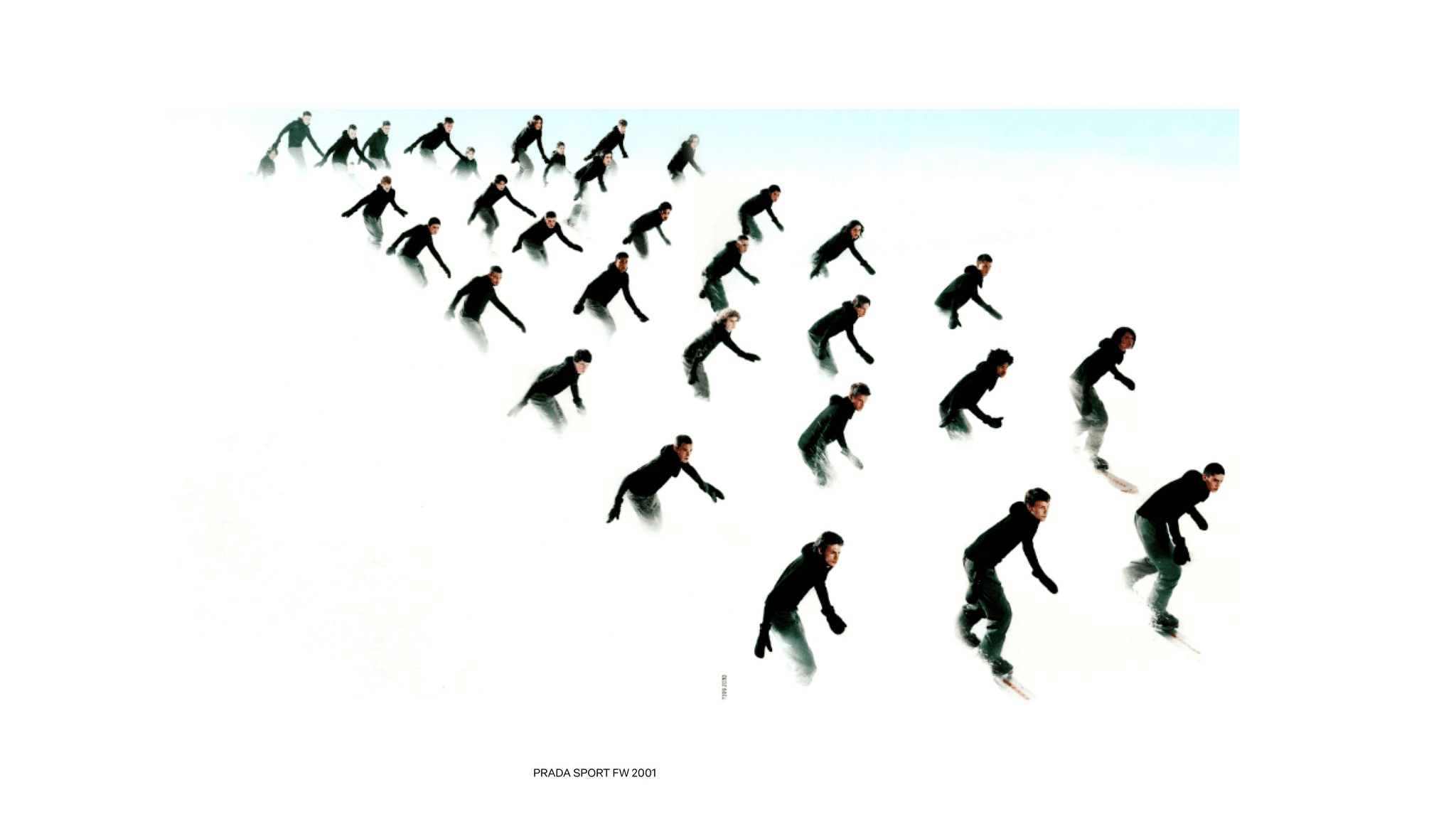

Prada Sport is a good bridge between outdoor modular logic and luxury finishing because it applies “kit” thinking to a single garment: the Spring/Summer 2000 convertible jacket uses zip-off sleeves so the same piece can shift from long-sleeve jacket to short-sleeve or vest-like wear, while keeping the construction looking intentional rather than improvised (the hardware and finish are part of the design, not an afterthought).

That same logic becomes even clearer at a larger scale in military clothing, where modularity is written as a full system: the U.S. Army describes GEN III ECWCS as a 12-piece kit that lets soldiers choose from seven layers depending on mission and environment.

FOOTWEAR, THE PRESSURE POINT

Shoes are inherently assembled, but modularity is what brings that assembly to the user. Take Marc Newson's Nike Zvezdochka, a modular sneaker known for its design around four interlocking parts. It's a system built to lock together, not just exist as one permanent form.

The example of footwear suggests that a connector is considered a necessary element of a product's design when the product is intended to change form.

Issey Miyake, built into the cloth

Most modular fashion is described as swapping parts. Issey Miyake’s A-POC (A Piece of Cloth) has a different approach: modularity through format.

Rather than attaching and removing components, A-POC uses continuous textile structures designed so garments can be cut out from the cloth, shifting completion into a planned action by the wearer.

Modularity can be about parts that connect. It can also be about systems that produce multiple outcomes from one structure.

BUILT TO KEEP GOING

Modularity connects to sustainability when it changes what happens to a garment over time. If one component fails, the whole piece does not have to fail. If needs change, the garment does not have to be replaced by default.

Across maintenance, couture, outdoor kits, techwear systems, footwear connectors, and A-POC’s production format, the through line stays structural: parts are designed to separate and return without the garment losing integrity.